About the Callicoon Business Association

Callicoon History

Dutch hunters traveling west from the Hudson Valley first settled the area in the 1600’s. Here, they found a location on the banks of a river where, among other sources of food, there was an abundance of wild turkey. They marked this location on their maps as “Kollikoonkill,” meaning “Wild Turkey Creek.” The area became a prime source for fresh-cut timber and the Delaware River served as a natural access to the populated coastal centers of the east. During the 1760’s, timber rafting began, where tree trunks were lashed together and floated to sawmills downstream. Then, in the 1840’s the Erie Railroad opened up the area, laying tracks along the banks of the Delaware River to link the Great Lakes with the Eastern Seaboard. In honor of the centrally located railroad station, the townspeople renamed the town Callicoon Depot.

Although the hamlet dates back to the 1600’s, very few buildings are older than 1888, a date etched in Callicoon history forever because of a devastating fire that nearly wiped out the entire Main Street. The resilient community immediately rebuilt, replacing every building by year’s end. Today, visitors and new residents are drawn to the pristine beauty of “Callicoon-on-the-Delaware” as they enjoy one of the last wilderness regions with a rich and colorful history.

Practically all of the land now within the boundaries of the Town of Delaware was a part of the tract of the Hardenburgh patent purchased in London about 1750. The buyer was a New York distiller named Joseph Greswold, who had traveled to England in search of a second wife. While in England he saw an advertisement listing lands for sale in a section of the Province of New York in North America known as Hardenburgh Patent Number One. Upon investigation he purchased two parcels that are now comprised of Cochecton, Callicoon, Hankins and Kenoza Lake at a price of about $10,000. This territory was rough, heavily wooded and only accessible via narrow trails and the Delaware River, which was not a navigable stream at that time. In 1755 or 1756, Greswold hired Joseph Ross of Bound Brook, New Jersey, to settle at the confluence of Callicoon Creek and the Delaware River near where the current cemeteries are located. Acting as Greswold’s land agent, he built a house near what was Upper Delaware Campgrounds.

When Ross arrived at what came to be known as Callicoon, there were few settlers in the area, none within a mile of his new home. Many years before, hunters from the Hudson Valley had ventured into the valley of the Callicoon Creek, finding abundant wild turkey and naming the waterway “Kolikoonkill” (cackling hen-turkey stream). A fellow Greswold employee by the name of David Young and his family settled just downstream at Big Island, with William Conklin and his teenage wife Betsy living nearby. They cleared the flats along the Delaware and began to develop their farms.

With the onslaught of the Revolution and Indian/Tory raids on the frontier, virtually all settlers fled the upper Delaware valley. Ross, who was a loyalist and a friend of the Mohawk chieftain Joseph Brandt, was especially threatened by his passionately patriotic, occasionally vindictive, neighbors. He returned to Bound Brook, but later came back to his upper Delaware farm after the war ended.

Edward Greswold a NY lawyer and son of Joseph Greswold, acquired land from his father and erected a mill on the site of Roche’s Garage storage building area. In addition to the mill, Greswold also built a barn and blacksmith shop with the intent of starting a village. This venture was unsuccessful; however, it was from this site that the village of Callicoon later grew. In 1890 Martin Hermann erected his mill and established a lumber business on the site of the original mill along the Callicoon Creek

Not long after Ross’s first settlement, the lumber rafting industry came into being. It began in 1764, when Daniel Skinner put his first small raft of logs into the Delaware just below Callicoon, and floated it to market in Philadelphia. This grew into a business, which took millions of board feet of timber from the virgin forests of the Upper Delaware to the fast growing cities of Philadelphia, Trenton, and Easton. The rafting industry peaked in 1875 with approximately 3,000 rafts floating downriver for sale that year. By 1922, when the last raft came into Martin Hermann’s mill at Callicoon, the industry had dominated the area for more than 150 years. It drained the region of its native timber, and in the process changed it from a forested wilderness into a relatively civilized world of dairy farms and small communities.

As the forests were cleared, other communities began to appear. Hortonville was settled by Charles Layton – a friend of Joseph Ross’s – in 1790. About 1849, Charles Horton built a tannery there. Horton & Clements Tannery remained in business until about 1873, using tannin extracted from the bark of the hemlock trees to treat hides, creating leather for boots, straps, and belts to run the machinery created by the Industrial Revolution. Manufacturers of leather found it more profitable to take the hides for curing to the localities which produced hemlock bark than it was to haul the hides to the leather factories. For many years there was more sole leather produced in Sullivan County than in any other territory of equal extent in the world.

Other tanneries were erected in Fremont Center, Callicoon Center and Kenoza Lake. The tanning industry prospered for about 40 years until it was interrupted by the Civil War.

Later, Henry Gardner and Asa K. Osterhout converted the tannery at Hortonville into a paper mill, under the name of Gardner, Osterhout & Co. They first made what was known as straw paper, a course wrapping paper. They bought all the straw that the local farmers could supply and brought in large carloads from western New York as well. Later they made tissue paper from wood pulp and waste paper, which was acquired from department stores. This industry was abruptly terminated in January 1879 by a disastrous fire which destroyed the mill and adjoining buildings.

Callicoon Depot, as it was first known, did not exist until the building of the Erie, America’s first long line railroad. During construction of the Erie’s Delaware Division, completed in 1848, the settlement served as one of the staging areas and was formally named in recognition of its railroad depot. In 1906, the U.S. Postal Service dropped the “Depot” from its name and it became simply Callicoon.

The coming of the railroad had a huge impact on the area, bringing German immigrant farmers to populate the Beechwoods northeast of Callicoon. These people proved to be the real backbone and living spirit of the whole area that they had settled. With only the use of manual tools, they cleared farm land from vast forests and began the rich heritage of farming in the local community. Early Beechwoods settlers were: Jacob Kaufman, Christian Kautz, Josiah Deuner, Friedrich Allgeier, Jacob Schumacher, Charles Fischer, Curtis Layton, John Bauernfeind, John Marsh, and Christian Weintz.

Kenoza Lake (Pike Pond) had begun to develop before the advent of the railroad. The first settler there was a man named Woodruff, who came in from Poughkeepsie in 1812. Other early settlers included Stephen Gidney, who arrived from New Paltz about 1820, and Captain Nathan Moulthrop, a War of 1812 veteran, who came to the area in 1828. In 1833, Eli Beach, William Bonestel, John Bied, and Robert Burger built a tannery there, which was later operated by Gideon Wales for many years. As the area developed, the government also changed. Prior to the Revolutionary War, much of the territory that is now Sullivan County was the Town of Mamakating. The Town of Lumberland – including today’s Towns of Bethel, Highland, Cochecton, Liberty, and Tusten – was formed in 1798. In 1869, the Town of Delaware was taken from the Town of Cochecton.

The first supervisors of the Town were Isaac R. Clements (1869), a tanner from Pike Pond (Kenoza Lake), William H. Curtis (1870), a businessman from Callicoon Depot, and John F. Anderson (1873), an attorney also from Callicoon Depot. William H. Curtis has the distinction of being the only man to serve as supervisor for two Sullivan County towns, having been supervisor of the Town of Cochecton 1850, 1853, 1857, and 1859.

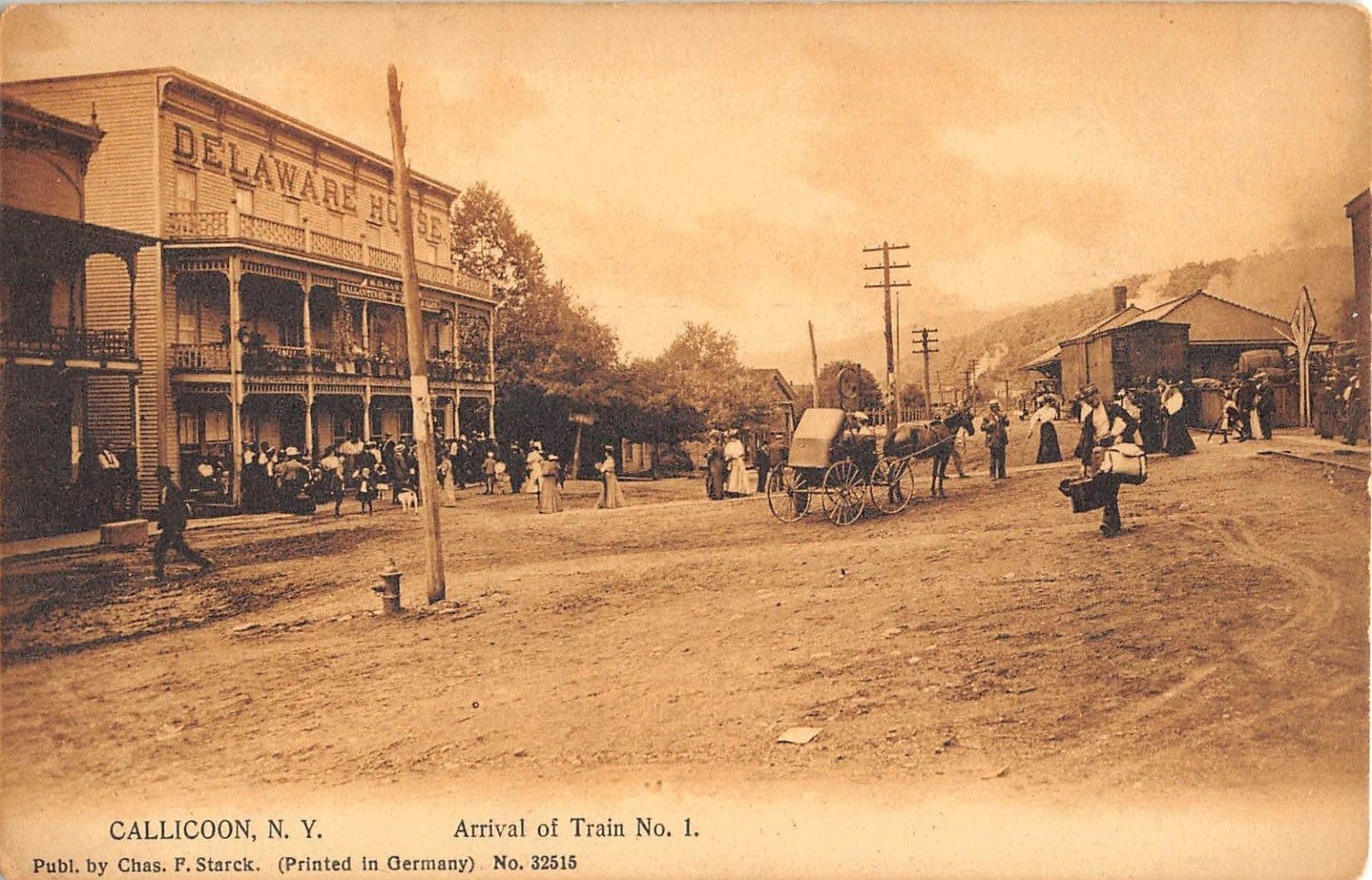

Callicoon grew into a busy and prosperous community, with the railroad station as the center of the community. At one time, it boasted five hotels, as well as a harness maker, livery stables, a dry goods store, two grocery stores, a milliner, a large sawmill, a newspaper, a pharmacy, a jewelry store, and at least two saloons. One of the latter had a special “ladies entrance.”

Following a great blizzard in 1888, on February 28, 1888 a massive fire destroyed most of Main Street Callicoon. Nearly all those businesses affected, rebuilt in a larger and more substantive manner.

In 1899 a bridge was erected by The Horseheads Bridge Co. of Horseheads, NY, at a cost of $23,180.00. It spanned the Delaware River from Callicoon to Pennsylvania, enabling those living on the other side of the river access to the town. The bridge was ready for traffic on January 16, 1899 and served as a toll bridge for 25 years. In 1924 it was purchased jointly by the State of New York and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and became a free bridge.

In 1904, the privately owned Callicoon Water Company was established, bringing spring fed water to an enclosed reservoir serving the community.

In 1906, the Western Sullivan Telephone Company was formed at Callicoon. This company served the territory in the towns of Delaware, Cochecton and parts of Bethel Township, Callicoon and Fremont. It was bought in 1926 by the New York Telephone Company.

In 1908 Dr. Frederick Cook of Hortonville attained the North Pole, bringing notoriety to our small corner of the world.

In 1914 the first venture in electric lighting was organized by Theodore Cook (Dr. Cook’s brother) of Hortonville. To create power, Cook first built a dam across Callicoon Creek near his home. But the dam failed to hold. Cook then manufactured the electricity by steam power, and provided electricity to Callicoon for several years.

Each of the communities had churches established in the 19th century: Lutheran in Kohlertown; Methodist in Kenoza Lake; Reformed/Presbyterian in Hortonville; Methodist, Episcopal, and Roman Catholic in Callicoon. Catholic priests, who came to the area ministering to the 19th century German and Irish immigrants, paved the way for establishment of St. Joseph’s Seminary. In 1901, the Order of Friars Minor, Franciscans based in Patterson, New Jersey, bought a large boarding house property overlooking Callicoon Depot. There they built an imposing seminary, the largest native bluestone building in the area. From that time until the 1970s virtually every Franciscan in the Province passed through St. Joseph’s Seraphic Seminary, either as student, as teacher, or both. Finally closing due to a drop in student enrollment, the complex was sold to the U.S. Department of Labor, which operates it as a Job Corps Training Center.

The communities that came to life nourished by the railroad found their economies badly damaged as railroad travel gave way to the automobile. The building of New York State Route 97 in 1939 as a scenic highway did not immediately lead to an influx of new visitors. By the 1950s, the boarding house and hotel business was fading from the scene. Beginning in the late 1960s, a new kind of tourism found its way to the town. Campgrounds and canoe liveries, followed by bed and breakfast inns, drew a new generation of vacationers. As the forests grew back and the river valley remained remarkably pristine, increasing number of visitors were drawn to the area.

Federal legislation in 1978 created the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River. Encompassing the western section of the town, this unusual unit of the National Park System was established as a partnership park, relying upon local zoning to protect the land of the river valley, with the National Park Service as a partner primarily focusing on management of the river itself – monitoring water quality, enforcing law on the river, and encouraging environmental sensitivity.